Ameelio, a nonprofit startup that intends to replace inmate-paid video calling in prisons with a free service, is making inroads against the companies that have dominated the space for decades. With nine facilities in Iowa up and running and talks progressing with dozens more ahead of a planned 2022 launch, the company may soon usher in a fundamental change in how incarcerated people access communication and education.

Founded less than two years ago, Ameelio had its sights set on the calling system from the start, but began by offering a web and mobile service to send letters to inmates, which ordinarily is a surprisingly difficult process.

“We maybe had 8,000 users when we spoke to you, and a few months later we launched our mobile app. Now we’re hosting something like 300,000 users, in every state and some territories,” said Uzoma Orchingwa, founder and CEO of the company. But while letter writing is a useful service, the team’s efforts have been focused on developing and testing the suite of digital products they hope to offer across the country starting next year.

By building their own tech stacks and shifting the resulting (much lower than market) costs away from inmates, Ameelio provides an enticing alternative to the totally outdated systems in most prisons today.

Many may not be aware that a handful of for-profit companies perform nearly all of the for-profit video-calling services used by the nation’s often for-profit prisons, which collect a share of this tainted revenue. Securus and Global Tel have provided calling services for a long time, and their business practices were described by former FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn as “the clearest, most glaring type of market failure I’ve ever seen as a regulator.”

Despite costing nearly nothing to provide, calls can cost inmates as much as a dollar a minute — extortionate 10 years ago but positively criminal today, when free video calling is a basic feature we all expect for free or a nominal charge. The deeply unpopular Securus is in the middle of a rebranding (to “Aventis”) and potentially a SPAC deal to reinvent itself and purge the past, following the example of Facebook and Blackwater. But the zebra can’t change its stripes, and all that.

Not only that, but customers — that is to say, the Departments of Corrections that contract with these businesses — are beginning to doubt the value of the services being provided. The pandemic resulted in a suspension of in-person visits and their temporary replacement with free video calls, and Ameelio’s CTO Gabriel Saruhashi said that many a DOC would prefer to keep it that way. The old, and rather unethical, method of charging inmates and sharing the income is growing increasingly indefensible in the modern era, and they are more interested in keeping things simple.

Orchingwa explained that they’ve structured Ameelio as a turnkey system for whatever level of involvement a facility or department chooses. The cumbrous RFP system for selecting providers of state-paid services can be a barrier to adoption at scale, but Ameelio can be used as a basic replacement for free video calling platforms like Google Meet; in fact, Louisville Metro DOC has made the switch to free communications with Ameelio without any need for legislation, an important precedent to explore. Later on, if desired, the company can also provide the required and regulated scheduling, storage and security services for a fee.

This would come in far, far below quotes from existing providers. That’s because the entire problem has changed from being a telecoms problem to a tech problem, and “They aren’t tech companies,” Orchingwa said. “Their products haven’t changed in two decades.”

Instead, they buy companies to bolt onto their existing services or pay for off the shelf tech like Twilio. So in order to pay for the service in the first place, then provide the state its cut, and still come out ahead, they have to charge as much as the market will bear. And since the market consists of largely disenfranchised incarcerated folks and their families — not exactly the lobbying type — complaints can be written off more or less completely. The result is poor service at maximum price.

“We don’t have that pressure,” said Orchingwa. “We’re a lean startup, and we do everything in house.”

“We leverage a lot of open source tech, which is part of why our costs are so low,” said Saruhashi. “They use Twilio, we use mediasoup; the only thing we’re paying for is servers. And we use Kubernetes, so our total cost right now is like $100 a month.”

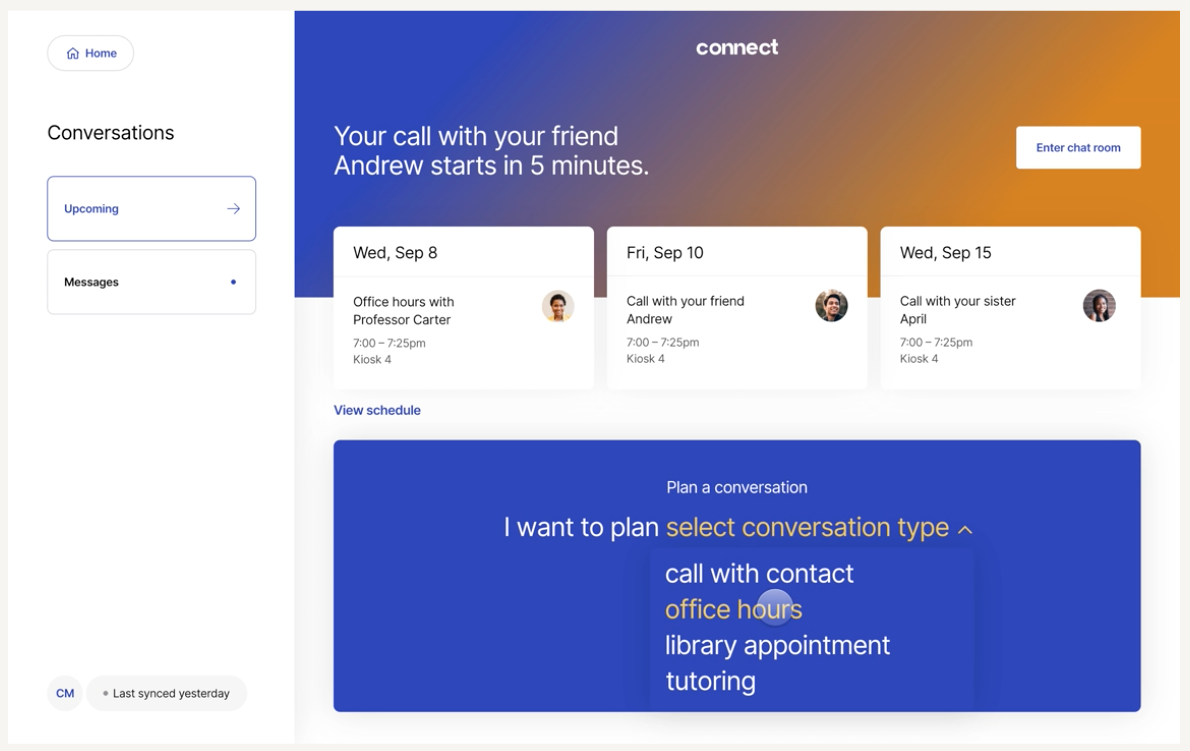

They’ve also done their own hardware, standard Android tablets with custom enclosures that can very easily be provisioned and deployed anywhere there’s Wi-Fi. Facilities looking to replace landlines love that they can decommission a dozen phones and bring on five dozen tablets, through which both video and audio calls are possible. Video calls must be scheduled and recorded (by Ameelio or another), but audio can be done any time, and having one service and one device do both streamlines things.

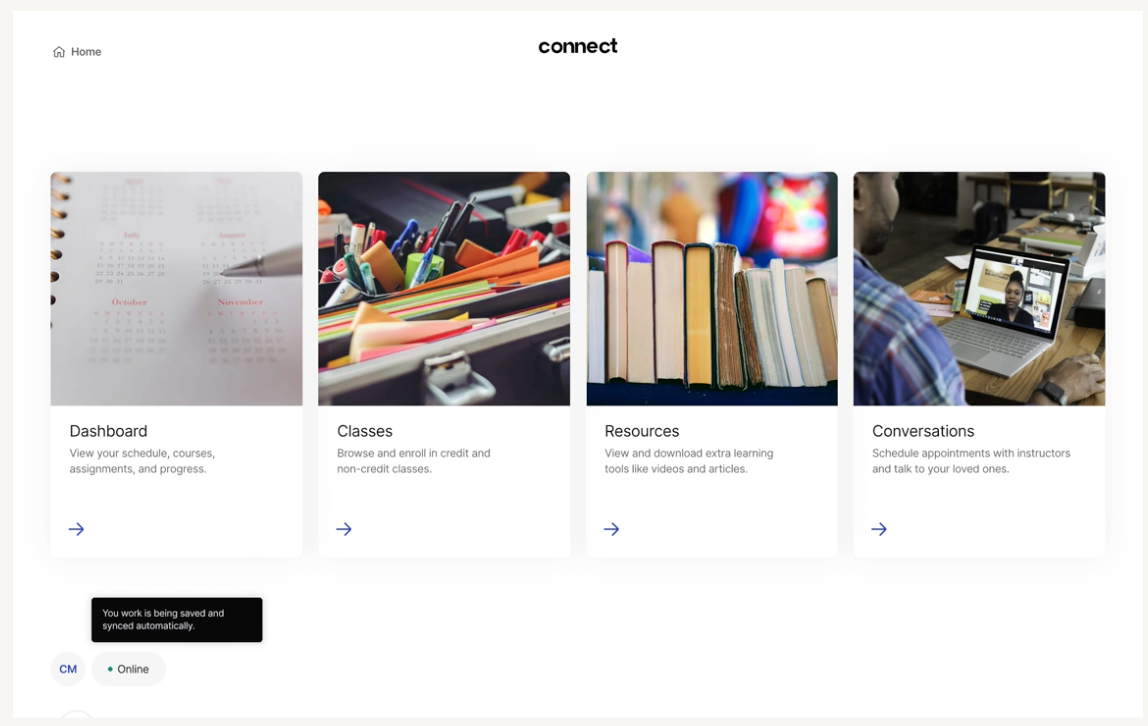

The last area where Ameelio hopes to move things forward is in education. Currently there is a real hodgepodge of education systems available to inmates. Sometimes security requirements mean paper resources or homework must be physically brought and collected by a representative of the school (something we talked about at TC Sessions: Justice this summer). Some places there is a virtual service, but only accessible at certain times, or with limited topics. As interesting as a course on English Literature might be, not every inmate is interested in completing their BA, possibly preferring to learn a trade.

The same tablets that provide audio and video calls — and of course other services like telehealth, official communications, text-based messaging and so on — would be the platform for education or simply reading. Orchingwa said there is great interest from both sides of the market (educators and DOCs, to say nothing of the inmates themselves, who have fought for this for decades), but that digitization has been a slow process.

“There are grants available, but no education platform,” he said. “The news is Ameelio is actually doing it, at two facilities and we just signed our first county. LinkedIn Learning, MasterClass, PBS, we’re uploading thousands of books from Gutenberg. We’re also trying to do job training; we identified CDL [commercial drivers license] training as being of interest, and we’ve been running that on the outside with about 50 formerly incarcerated students with computer literacy issues, using the app to study.”

It’s all still very much on the horizon, but it’s telling that in the short time since its founding Ameelio has already clawed away numerous facilities from industry incumbents that got their start in the ’80s. This is an industry ripe for change and there are plenty of stakeholders willing to try something new, even if it means rocking the boat a bit.

Although Ameelio does intend to fund itself by acting as the provider for commercial services states already pay for (recording and storing video calls) and by charging attorneys for secure, private calls instead of inmates or families, it will remain free to users. “Ameelio will always exist as a nonprofit. We are committed to never charging families to communicate with their loved ones and will always keep our services that face incarcerated people as nonprofit. We don’t believe that a for-profit model that relies on incarcerated people is justifiable,” Orchingwa said.

It does help to have a few deep-pocketed allies, though. Orchingwa mentioned Jack Dorsey, Vinod Khosla, Eric Schmidt, Brian Acton, Sarah and Rich Barton, Devin and Cindy Wenig, Kevin Ryan and Draper Richards Kaplan as those who are presently supporting Ameelio, and that True Ventures has awarded it grants as well. The company is working on a planned $25 million round to get them through the next few years as they establish their own income streams.

The idea that an incarcerated person could — and should — have a device that lets them communicate securely and even spontaneously with their loved ones and legal representation, as well as access educational resources and other services, seems like a fairly self-evident one. But the market, and the lobbying and industry that define it, have thwarted this path forward for a long time. Ameelio is just now building momentum but in a few years may be the provider of a free (as in beer, as in speech, perhaps even as in FOSS) platform that provides it for this perennially mistreated population.