Wellness startup Bellabeat, which has primarily marketed its wearable health trackers to women, recently introduced Ivy, a stylish, comfortable health tracker with a long-lasting battery life, poised as a prettier version of a Fitbit. But the accompanying subscription “Coach” software supporting the new bracelet feels like it’s still in beta, which is concerning for a product aiming to offer health guidance to real-world users.

Over the past eight years, Bellabeat has established a track record of releasing wearable devices that look attractive enough to wear as everyday jewelry, like its Time smartwatch and Leaf health tracker. Ivy, launched this September, aims to be its most comprehensive product yet — tracking sleep patterns, heart rate, menstrual cycles, steps, hydration, activity, mindfulness and more.

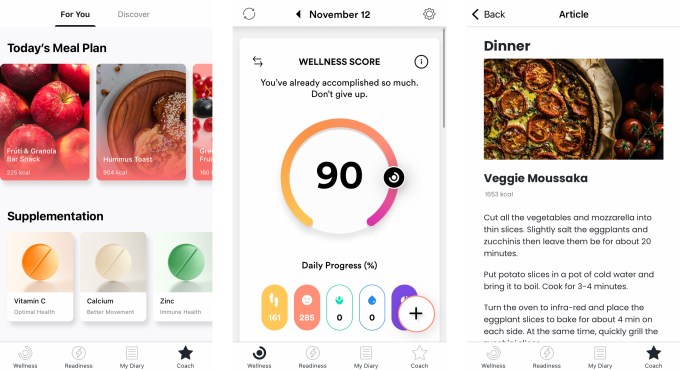

As a simple health tracker, the Ivy succeeds in what it sets out to do, by tracking your sleep, heart rate and steps. Based on your daily achievements, the app gives you a wellness score. While it encourages you to exercise, it also encourages you to set aside time for daily meditations and other fun activities, which can range from reading to playing sports to going shopping. You’re also presented with a readiness score, which is calculated based on ongoing analysis of your heart rate, resting heart rate, respiratory rate and cardiac coherence.

But at $250, the Ivy isn’t cheap — especially when most of us have a free pedometer built into our cell phones. Yet the device is in such high demand that current orders won’t ship until the end of November — the company sold more than 50,000 units in its eight-month preorder phase, and over 18,000 since launching in September. Across its various products, which sync with the Bellabeat app, the company has over 100,000 monthly active users. It’s clear that the Y Combinator alum is onto something with its premise: women are interested in health tech, but they don’t always want to wear a tracker that makes them feel like a cyborg.

Nutrition glitches

When you onboard onto the Bellabeat app, you’re presented with three main goals to choose from: “weight loss,” “get fit” or “get healthy.” Then, you can select from supportive goals: “better sleep,” “healthy aging” and “better sex.” Bellabeat’s premium “Coach” service — which sells for $99 per year — offers daily meal plans and weekly shopping lists to help women eat a balanced diet.

When TechCrunch tested the service, we selected “get healthy” as our main goal and were presented with meal plans that regularly averaged about 1,500 calories per day. We changed our goal to “weight loss,” and found the daily meal plans remained about the same.

TechCrunch asked Bellabeat why its standard meal plans were just 1,500 calories. A representative for Bellabeat told us the meal plans were generated due to a bug in the app, and to check it again. Upon returning to the app, the recipes were filled with inconsistencies, however. In one recipe, hummus on toast amounted to a shockingly inflated 904 calories, while veggie moussaka appeared as 1,653 calories, equal to about three McDonald’s Big Macs. When TechCrunch followed up about this, the representative said that the company was still working out some kinks with the app. But the app was not presented to us as a beta — the product is already on the market, retailing for $250 with a $99 yearly subscription. Even users who aren’t subscribed to the Coach service can still see recommended meal plans and the calorie counts for those meals. But when you upgrade, you get full recipes, as well as many exercises and health videos.

Image Credits: Bellabeat screenshots by TechCrunch

To be clear, Bellabeat isn’t marketing itself as a calorie-counting app in the same way that apps like Noom or MyFitnessPal are — the latter apps are food diaries, asking users to input everything that they eat in a day. Research suggests that apps like MyFitnessPal are widely used among people with eating disorders, as they can enable restrictive habits. Noom, meanwhile, claims to be anti-diet, but is said to offer small daily calorie allowances which can be connected to the onset of eating disorders, or harmful for people recovering from an eating disorder. Plus, since these apps can scan barcodes of packaged foods to determine exact calorie counts, some users report feeling encouraged to choose processed foods over homemade meals — it’s easier to know how many calories are in a frozen dinner than in one you make yourself.

However, even though Bellabeat doesn’t ask users to input everything they eat in a day, the not-so-subtle implication of its recommended meal plans is that you shouldn’t be eating more than 1,500 calories per day, which can be harmful. According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, women should eat between 1,600 and 2,400 calories per day. Exact daily intake recommendations vary depending on an individual’s lifestyle and various other health factors.

“What frustrates me the most about health trackers that recommend a low-calorie allowance is that they do not take into account important factors about the individual using the app. They spit out a general number, and in this case, the same number for both weight loss and weight maintenance, with limited science behind it,” said Gabi Kahn, MS, RD, who specializes in nutrition for mothers. “Apps like these that recommend a 1,500 calorie diet to every woman are promoting disordered eating. They lead to people obsessing over every calorie they consume, overthinking every food choice to the point of obsession and overanalyzing every bite of food they eat.”

Wellness gone awry

Women’s wellness is a tricky industry and one undergoing more scrutiny in recent years about its messaging to women. The rebrand of “Weight Watchers” to “WW” (with the tagline “wellness that works”) is indicative of a larger trend in marketing health products to women: instead of telling women to lose weight, these companies tell women to be healthier. This cause sounds noble enough, yet it perpetuates the false idea that weight is the only indicator of health, rather than just one data point amid many factors. And as the industry shifts away from weight loss and toward the more sanitized “wellness,” lawmakers are paying close attention to link between social media apps and eating disorders, and particularly their impact on the mental health of minors.

Bellabeat is targeting a similar market. The company said that most of its clients are between the ages of 25 to 55, with 66% falling between ages 28 and 44.

Though Bellabeat does work with a team of 14 medical professionals — including a nutritionist — that expertise is easily undermined by these technical difficulties. Since reporting the bug to Bellabeat, the number of calories in these daily meal plans has increased to a more reasonable value for weight maintenance. But at the time that TechCrunch tested the product and was served these low-calorie meal plans, Ivy had already been on the market for about two months and sold almost 70,000 units. Solving such massive bugs at that point is dangerous for a product that women are using to make decisions about their health.