Prellis Biologics, a company developing the tools to create 3D printed organs, announced a $14.5 million Series B round on Wednesday. Prellis has spent years developing tissue engineering capacity, but has focused recently on developing one type of structure in particular.

Up until this point, Prellis has focused on 3D printing vascular scaffolds that would allow companies to grow healthy and oxygenated human organs (or miniature versions, called organoids) for drug testing, and eventually transplant. But the company has recently debuted a new product, called EXIS (short for Externalized Immune System): a lab-grown version of a human lymph node.

Lymph nodes are critical parts of the human immune system – they store certain immune cells, and help the body manufacture immune responses. Ideally, those lymph node organoids would aid in drug development by mimicking how a person’s immune system might respond to new treatment. And, perhaps, help create some new drugs along the way.

“By creating this immune system in a dish, we can actually test if those therapeutics are going to elicit an immune response before it goes into a human,” founder and CEO Melanie Matheu told TechCrunch.

“Our company’s edge is that [EXIS] is out of the box fully human.”

Prellis Biologics, founded in 2016, has raised about $29.5 million to date. This Series B round was led by Celesta Capital and existing investor Khosla Ventures. In addition, the company will add Kevin Chapman, Celesta advisor and former CSO of Berkeley Lights, as Chief Scientific Officer. Yelda Kaya, formerly of J&J Innovation, will join as Chief Business Officer.

Lymph node responses to drugs or pathogens has been recognized as a way to predict how the whole immune system might react. Correspondingly, a number of academic labs working on developing in-vitro models of human lymph nodes – from lymph nodes on chips, to growing lymphoid organoids from tonsil tissue.

Prellis has entered the fray by using its scaffolds to facilitate oxygen and nutrient exchange needed to grow functioning lymph node organoids. This method, Matheu says, allows Prellis to “replicate the human immune system outside the human.”

This focus on the lymph node, in turn, opens up new angle for the company: antibody drug development.

Developing new antibody treatments and predicting how they’ll work in clinical tests is becoming a more competitive space, and there are a few different approaches underway.

Some are computational. Nabla Bio, which just raised a $11 million, has used natural language processing to design antibodies. Generate Bio, which just raised a $370m Series B, has also used a machine learning approach.

Prellis’ approach is to model the immune system in miniature and develop a cadre of drug candidates by mining immune responses. Matheu calls it “natural intelligence” as opposed to artificial intelligence.

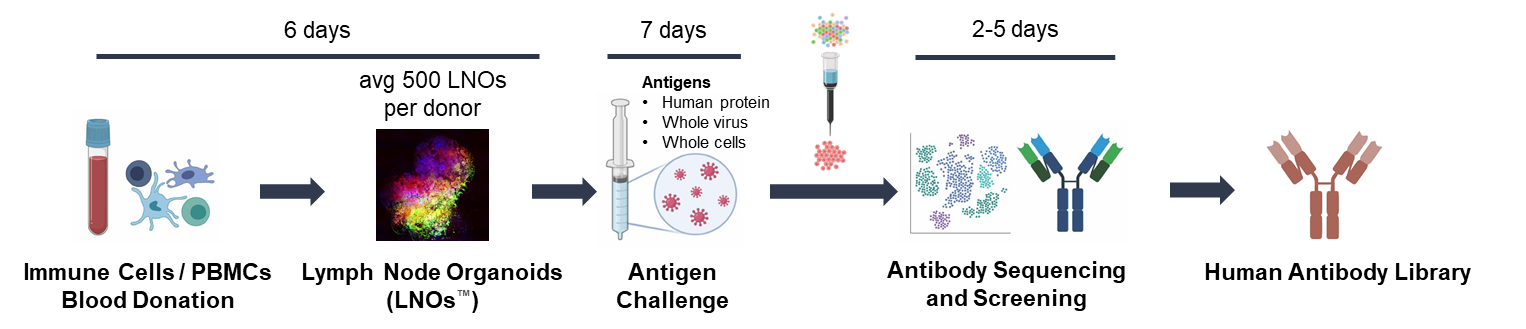

The company can create 1,200 organoids from one blood draw, challenge those immune systems with a particular antigen, and see what each immune system comes up with. That process, she says, can be done with different blood donors with different immune system characteristics to create a plethora of responses to analyze.

“It’s very rare that all 10 of those people are going to come up with the same antibody solution to the problem of: does it bind this protein? And so from a given human, we’re averaging anywhere from 500 to 2000 unique antibodies, and then you just multiply that by the number of people, and these are all target binding antibodies.”

It takes about 18 days to go from blood draw to “antibody library,” per materials provided by Prellis Biologics.

Image Credits: Prellis Bio

Matheu says the company has developed antibodies responsive to SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A and Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (these results haven’t been published). It has also entered into partnership with five drug companies, though Matheu declined to name which ones.

The company plans to use this round to move from an R&D driven company to a product focused one – which means developing more drug partnerships, and demonstrating the platform’s capability.

The major marker of success, she says, would be to bring an antibody treatment into the clinic. That may occur through collaboration with a pharmaceutical partner, though the company hasn’t ruled out creating a drug pipeline of its own.

Matheu is light on specifics, but says Prellis is developing “internal technology” that would support a therapeutic pipeline.

“I will say, we will move in that direction as the technology develops,” she said.