Peter Beck’s earliest memory is standing outside with his father in his hometown of Invercargill, New Zealand, looking up at the stars and being told that there could very well be people on planets orbiting those stars looking right back at him.

“For a three or four year old, that was a mind-blowing thing that got etched into my memory and from that point onwards, that was me destined to work in the space industry,” he said at the Space Generation Fusion Forum (SGFF).

Of course, hindsight is 20/20. But it’s true that Beck’s career has been characterized by an unusually single-minded focus on rocketry. Instead of going to university, Beck got a trade job, working as a tool-making apprentice by day and a dilettante rocket engine maker by night. “I was very, very fortunate through my career that the companies I worked with and worked for, and the government organizations that I’ve worked for, always encouraged — or tolerated, maybe is a better word — me using their facilities and doing things in their facilities at night,” he said.

His tinkering matured with experience and working double time paid off: In 2006, he founded his space launch company Rocket Lab. Now, 15 years and 21 launches later, the company has gone public through a merger with a blank-check firm that’s added $777 million to its war chest.

$RKLB has launched! Today’s exciting next step in Rocket Lab’s story was made possible by the incredible people behind us — our team, our families, our customers, and our investors. Thank you, thank you, thank you. #SpaceIsOpenForBusiness #NasdaqListed pic.twitter.com/DLmVsmtqOj

— Rocket Lab (@RocketLab) August 25, 2021

The space SPAC craze

The merger with Vector Acquisition catapulted Rocket Lab’s valuation to $4.8 billion, putting it second (by value) amongst space launch companies only to Elon Musk’s SpaceX. SPACs have become a popular route to going public amongst space industry companies looking to secure large amounts of capital; rival satellite launch startups Virgin Orbit and Astra have each started trading via a SPAC merger, in addition to other companies in the sector, like Redwire, Planet and Satellogic (to name just a few).

Beck told TechCrunch that going public has been part of Rocket Lab’s plans for years; the original plan was to use a traditional initial public offering, but the SPAC route in particular enabled certainty around capital and valuation. According to a March investor presentation in advance of the SPAC merger — documents that should always be taken with a large grain of salt — the future is bright: Rocket Lab anticipates revenues of $749 million in 2025 and surpassing $1 billion the following year. The company reported revenues of $48 million in 2019 and $33 million in 2020, and anticipates hitting around $69 million this year.

But he remains skeptical of pre-revenue space startups, or those that failed to raise capital, using SPACs as a financial instrument. “There has been a lot of space SPACs go out, and I think that there is a spectrum of quality there for sure — some that have failed to raise money in the private markets, and [a SPAC merger] is the last-ditch attempt. That is no way to become a public company.”

While the space industry is relatively crowded now, with companies like Rocket Lab and SpaceX sending payloads to orbit and myriad newer entrants looking to join them (or, more optimistically, take their leading place), Beck said he anticipates the crowd thinning out.

“It’s going to become blatantly obvious to investors really quickly, who’s executing, and who’s aspiring to execute,” he said. “We’re in a time where there’s lots of excitement, but at the end of the day, this industry and the public markets are all about execution. The wheat from the chaff will get separated very, very quickly here.”

From Electron to Neutron

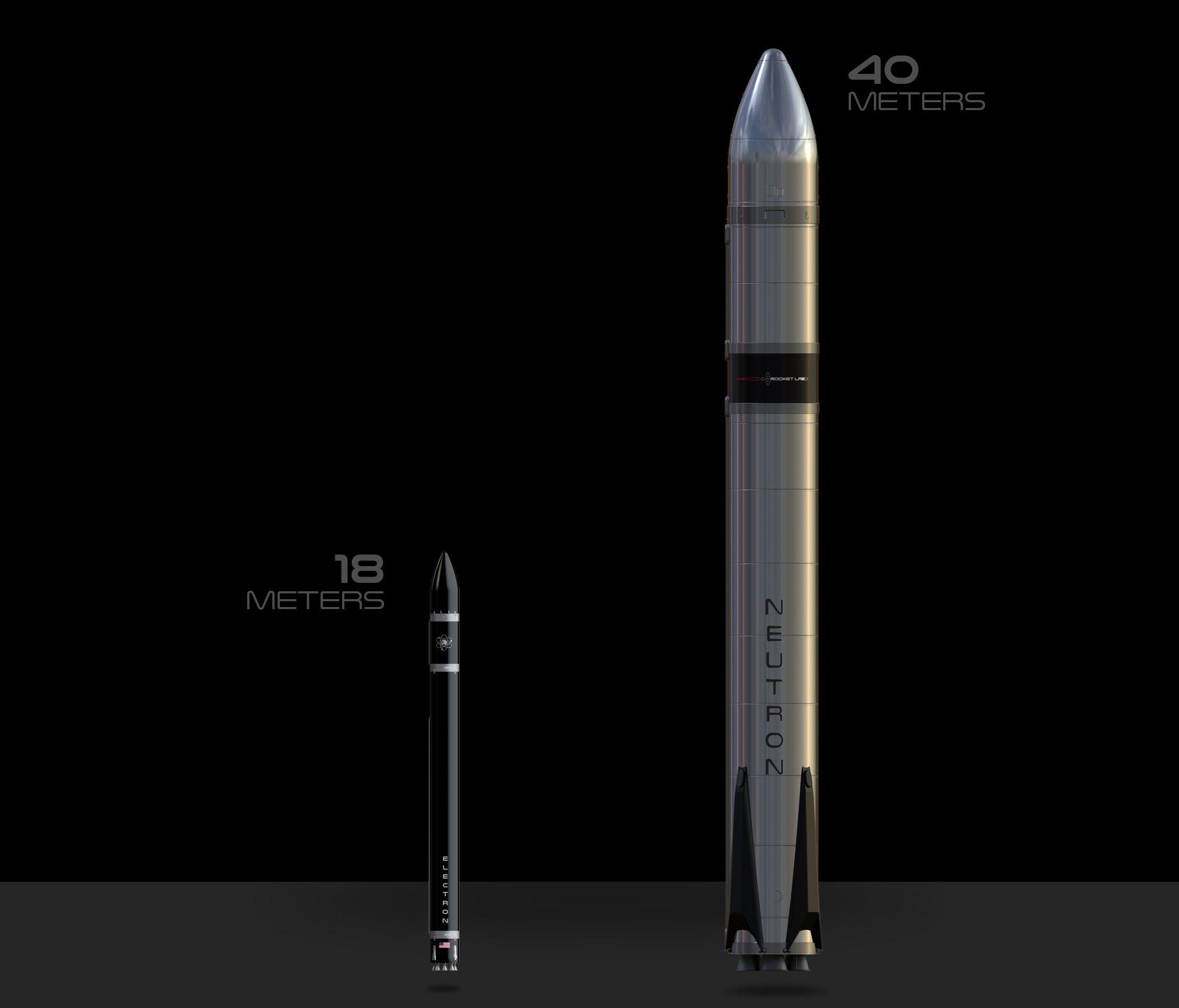

Rocket Lab’s revenues have largely come from the small payload launch market, in which it’s managed to take a leading position with its Electron rocket. Electron is only 59 feet tall and scarcely four feet in diameter, significantly smaller than other rockets going to space today. The company conducts launches from two sites: Its privately-owned launch range on Mahia Peninsula, New Zealand, and a launch pad out of NASA’s Wallops Island facility in Virginia (which has yet to play host to an actual Rocket Lab mission).

Rocket Lab is in the process of transitioning Electron’s first-stage booster to be reusable. The company has been implementing a new atmospheric reentry and ocean splashdown process that uses a parachute to slow the booster’s descent, but the ultimate goal is to catch it in the air using a helicopter.

Thus far, Rocket Lab and SpaceX have dominated the market, but that could change soon. Both Astra and Relativity are developing small launch vehicles — the latest iteration of Astra’s rocket is around 40 feet tall, while Relativity’s Terran 1 is in between Electron and Falcon 9 at 115 feet.

For that reason, it makes sense that Rocket Lab is planning on expanding its operations to include medium-lift rocketry, with its much-anticipated (and very mysterious) Neutron launch vehicle. The company has been keeping the details about Neutron close to its chest so far — Beck told SGFF attendees that even publicly released renderings of the rocket have been “a bit of a ruse” (meaning the image below bears little to no resemblance to what the Neutron actually looks like) — but it’s expected to be more than double the height of Electron and be capable of sending around 8,000 kilograms to low-Earth orbit.

Image Credits: Rocket Lab

“We do see a lot of people in the industry copying us in many ways,” he explained to TechCrunch. “So, we’d rather get a little bit further down the path and then reveal the work that we’ve done.”

Rocket Lab estimates that Electron and Neutron will be capable of lifting 98% of all satellites forecasted to launch through 2029, making the need for an additional heavy-lift rocket unnecessary.

In addition to Neutron, the company has also started developing spacecraft. It’s called Photon, and Rocket Lab imagines it as a “satellite platform” that can easily be integrated with the Electron rocket. The company’s already lined up Photon missions to the moon and beyond: first to lunar orbit for NASA, as part of its Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment (CAPSTONE) program.

Two Photons were selected earlier this month for an 11-month mission to Mars, and Beck has publicly discussed long-term plans to send a probe into Venus’ atmosphere via a Photon satellite.

Beyond Photon, Rocket Lab has also locked in a deal with space manufacturing startup Varda Space Industries to build it a spacecraft to launch in 2023 and 2024.

Neutron has been designed to be human-rateable right from the start, meaning that it will meet certain safety specifications for carrying astronauts. Beck said he’s certain that “we are going to see the democratization of spaceflight” and he wants Rocket Lab to be well positioned to deliver that service in the future. In terms of whether Rocket Lab would eventually expand into building other spacecraft, like landers or human-rated capsules, Beck demurred.

“Never, ever say never,” he said. “That’s the one takeaway I’ve learned in my career as a space CEO.”