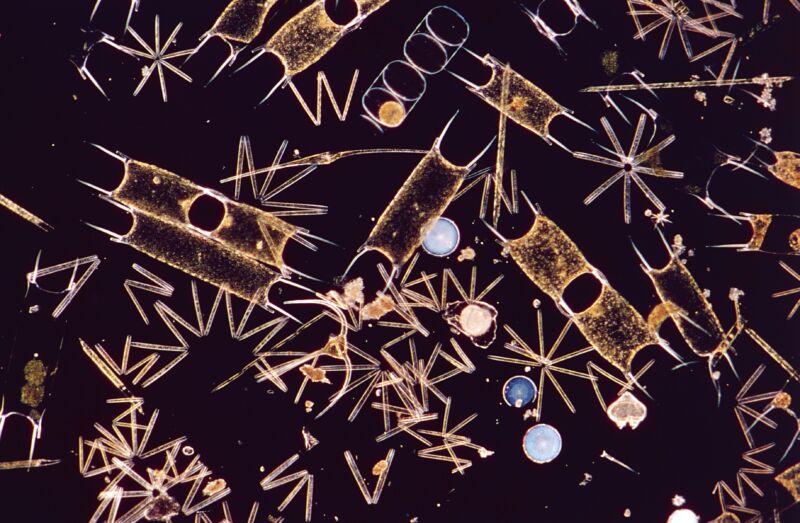

Enlarge / Microphotograph of thalassiothrix frauenfeldii, Thalassionemataceae, phytoplankton. (credit: De Agostini Picture Library | Getty Images)

On November 19, 1969, the CCS Hudson slipped through the frigid waters of Halifax Harbour in Nova Scotia and out into the open ocean. The research vessel was embarking on what many of the marine scientists on board thought of as the last great, uncharted oceanic voyage: the first complete circumnavigation of the Americas. The ship was bound for Rio de Janeiro, where it would pick up more scientists before passing through Cape Horn—the southernmost point in the Americas—and then head north through the Pacific to traverse the ice-packed Northern Passage back to Halifax Harbour.

Along the way, the Hudson would make frequent stops so its scientists could collect samples and take measurements. One of those scientists, Ray Sheldon, had boarded the Hudson in Valparaíso, Chile. A marine ecologist at Canada’s Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Sheldon was fascinated by the microscopic plankton that seemed to be everywhere in the ocean: how far and wide did these tiny organisms spread? To find out, Sheldon and his colleagues hauled buckets of seawater up to the Hudson’s laboratory and used a plankton-counting machine to total up the size and number of creatures they found.

Life in the ocean, they discovered, followed a simple mathematical rule: the abundance of an organism is closely linked to its body size. To put it another way, the smaller the organism, the more of them you find in the ocean. Krill are a billion times smaller than tuna, for example, but they are also a billion times more abundant.