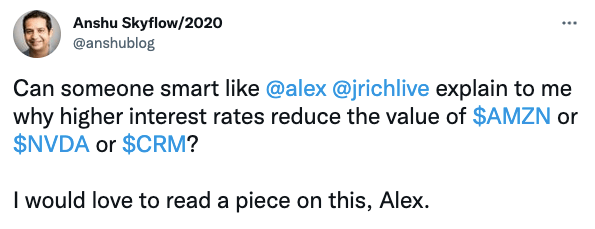

Investor and entrepreneur Anshu Sharma — formerly a partner at Storm Ventures, now CEO of privacy-focused SkyFlow — asked on Twitter today about the connection between interest rates and technology valuations:

Ignore the compliments; Sharma was merely trying to bait Jeff and me into engaging with his question. Which worked, as you can tell.

Sharma is someone with quite a lot of experience with both technology cycles and capital flows, so he’s not asking the generic question — he wants us to go a level deeper on the concept. So, let’s poke at the interest rate/tech valuations conversation.

History

One reason why startups are able to raise as much money as they are — record sums, recall — is today’s low interest rate environment.

Interest rates are slim around the world, which means that money is cheap. Cheap money means that you can hire capital for not a lot of cost. Coinbase, for example, is raising $2 billion in debt at the moment that will come due in two tranches. The first, due in 2028, will yield 3.375%, while the second half, due in 2031, will yield 3.625%. Coinbase raised its target from $1.5 billion to $2.0 billion thanks to investor interest. Money is inexpensive, so Coinbase is stacking a bunch of it on its side of the table from investors unable to find lower-risk, higher-yield places to stash their capital.

Cheap money means that you can’t expect much from loaning out your funds; bond yields are garbage today for that reason, which is great for companies like Coinbase and less great for capital pools in search of yield. Those same buckets of cash have gone fishing in other locales hoping for more profit per dollar, including the venture capital market. Ample capital has allowed venture capitalists to raise ever-larger funds, more quickly, and has allowed non-traditional investors to crowd into the startup market.

A good chunk of the unicorn boom is predicated on this cheap money moment we find ourselves in.

But nothing lasts forever, and with the U.S. government getting ready to start closing the taps on market-stimulating bond-buying and eventually raising the domestic cost of money by boosting the target range for the Federal Funds Rate, there is an expectation that certain assets will begin to lose some of their luster.

If money becomes more expensive, capital can make more money hiring itself to others; therefore, venture investing will become less attractive from a risk/reward perspective — again, in theory. At the same time, the stock market may reprice itself. Rock-bottom interest rates have led investors to buy up shares in growth-oriented companies because those firms were expected to have more valuation upside than similar investments into slower-growing companies were expected to post.

This particular trend hit its zenith last summer, when a number of industries were kneecapped by early-COVID restrictions and software stocks offered a way to still hunt yield through the prism of corporate revenue growth, payable not in a regular coupon disbursement but via market value accretion.

Cool.

In very broad terms, rising rates should make pouring capital into venture capital funds less attractive simply by making competing asset allocations more enticing. And rising rates may make the value-through-growth trade of public stocks less attractive as other shares cycle back into prominence.

There are technical explanations for the latter portion of our argument. Here are a few from the Sharma Twitter thread:

But Sharma is not really after that set of answers. He is instead questioning conventional wisdom. Why should it really be true, he’s asking, that tech stocks like Amazon and Salesforce will be worth less when rates rise — are they really worth less? In the Sharma worldview, rising software and e-commerce total addressable market has made those two companies worth more than was previously anticipated; why should those gains go away if money gets more expensive?

We have to move not in absolutes, but in basis points, to get the argument here. Interest rates, when they do change, will change slowly. It doesn’t seem likely that many governments are going to rapidly spin the crank on the price of money. Changes will come gradually, and with caution.

So aside from sentiment shifts that might lead to related asset price alterations, or wind up being more extreme than structural evolution, we shouldn’t really expect much change to the key dynamics of the market today when rates begin to rise. Or, more simply, a 25-basis-point change to the Fed target rate (0.25%) won’t mean much by itself unless more hikes are expected in a regular, rapid fashion.

The value of Amazon and Salesforce probably shouldn’t change much when the price of money starts to creep higher. If rates manage to hit 5%, then, sure, Amazon’s market cap will probably decline in relation to the value of other assets, but that’s more a comparative shift than a demand that Salesforce et al. lose value.

Sharma is arguing the base case with a wink. He’s a software bull. But his question does raise a good point for us to chew on: When the underlying factors responsible for part of the boom in the value of software and the wave of investment into software do change, how quickly will valuations change? (Put another way, when what’s driving relative price appreciation of growth-oriented revenues compared to other assets and dollars flowing into SaaS changes, how fast will the results of those factors shift?)

Those anticipating a dramatic repricing of tech valuations by initial, incremental shifts to the price of money, I reckon, are expecting a bit more of an exclamation point than they will actually read.

This is why The Exchange wrote the following the other week, when discussing the current startup boom and its potential durability:

But what we do think is possible to say with some certainty, or at least more than when a rebalancing of capital in the larger economy may occur, is that it will take a somewhat large shunt to knock the startup game off its current footing. Product demand coupled with funding interest is a killer combination for driving investment decisions — there’s capital chasing yield, and high-growth companies looking for capital. It’s a match made in heaven.

Moreover, many investors we’ve spoken to during this reporting cycle have been bullish about the quality of founders and startups they have the option of investing in. There’s not only market demand and capital, but what’s being built to answer the first with the help of the second is pretty good, at least in the view of the folks writing seven-, eight- and nine-figure checks to the startups in question.

All business cycles cycle. All things that go up eventually lose some altitude. But the appetite for startup shares and tech shares more broadly won’t come back to Earth at 1 g. Instead, a more lunar-gravity descent seems more likely. Pending something new, of course.